The Primer of Disbelief

It’s been said that childhood is getting longer. The rise of human development research, and the conception of adolescence as a developmental stage, introduce a gray area for how teenagers are viewed. A term was coined to describe the resulting point of view that adults operate from, illustrative of the consequent attitudes and actions that stem from the privileging of adult status compared with minors, a societal term for individuals under the age of eighteen. Adultism spreads the belief that adults have the right to operate on children and youth without their consent. The best version of this gives rise to nurturance and protection of children and youth, and an appreciation of the unique developmental needs and competencies that young people have. The worst version of this societal conditioning enables coercion, exploitation, dominance, and abuse. Cultural messaging, policy, and attitudes reflect this power arrangement between children and youth and adults, influencing our behavior and beliefs.

Consent is typically referenced in four key ways when youth are concerned. Age of consent. Informed Consent. Sober consent. And just, consent, meaning given or withheld agreement. This last form of consent is usually referred to as permission, perhaps permission by the young person, though more commonly referring to the permission of a young person’s caregivers. As with all consent education we approach defining consent in terms of sex. If we refer to consent in other situations, we’ve introduced legal, contractual, and criminalized meanings. If we refer to consent in reference to a minor, there are age specific clauses to consider, and adult perceptions of the young person’s judgment.

This is a depiction of a scene between a teenage daughter, Karen, and her father, the President, from the fourth season of Scandal. Forget what you know about the characters outside of this scene, and just read this dialogue to yourself as you watch the following clip. Read it, observe the scene direction, facial expressions, body language, and tones, and notice the recurring themes. Disbelief, control, resentment.

Father: “A sex tape? Karen is this true?”

Fixer: “Maybe we should wait for Mrs. Grant.”

Teen: “Yeah I want to wait for mom.”

Father: “No, start talking.”

Teen: “I just went to a party. Can we do this later, I’m still really wasted.”

Father: “She took drugs? She was high? This video, was she,” pausing. “Were you raped?”

Teen: “What?”

Father: “Honey, if you were it’s not your fault. It’s ok. You just have to tell us so we can make these boys pay for what they did to you.”

Teen: “Dad. I cut class. I ran away from my secret service goons. I helped some girl I barely know jack her father’s private jet to go to a party. I got drunk. I smoked weed. I shot up something awesome. And yet the only way you think I could have sex with two guys is if I were raped? How lame are you? What they did to me? What about what I did to them?”

Father: “You little!”

Fixer: “Fitz, the white house doctor is waiting downstairs for Karen. She needs a pelvic exam, an STI screening, a detailed talk about unprotected sex, why doesn’t she go do that now.”

Father: “Go, and then straight to your room. I want to know how she slipped her detail. I want every agent whose ever covered her grilled and I want heads on spikes you got that?”

Chief of Staff: “Yes sir.”

Father: “Maybe if I find a convent in Switzerland, I can stick her in it.”

Fixer: “That did not work when my father tried it with me. Angry, teenage, grieving girl with daddy issues, I relate.”

Father: “This is my daughter.”

Fixer: “Every girl is someone’s daughter.”

What strikes me about this scene are three clear diverging viewpoints. An incredulous teen asserting her bodily autonomy, even throwing it in her dad’s face. An overbearing parent grasping for alternative responsible actors besides his daughter. And a white flag toting adult ally, pointing out what’s ineffective about what this parent is focusing on.

There’s a reckoning happening and being resisted, because it calls into question the underlying assumptions that are being directly challenged while also clung to.

The daughter is holding her dad’s eye contact and intentionally aiming to provoke his anger. By calling out his selective read on her experience, she is demanding that he grant her agency within her first-person experiences. How she does this is by listing each individual choice that led up to the one he is most angry about; with her gaze she inserts,

· What about this feels less like me than those other choices?

· What is assuaged in you if this was an act of violence and not an act of desire?

· What about me having sex makes you angry?

· Why does the thought of me being raped leave you calm, and the thought of me choosing to have sex rouse you to fury?

He has no answer for her, only a more rigid attachment to his drive to place her somewhere where she’ll be safe, here defined as somewhere out of reach.

The first memory this scene conjured for me from my advocacy was a panel of youth survivors assembled as the keynote for a summit on sexual assault in high school I attended years ago. Speaking to an auditorium filled with faculty and students, four survivors shared their experiences of sexual violence. What they had in common was the fact that their experiences of violence were their first and only sexual experience, a point repeatedly emphasized and subconsciously assumed by listening adults.

The second memory this scene conjured is from a working group I participated on that was exploring what rights to advocacy youth survivors should have, particularly as it relates to confidentiality. In my first meeting, what was dwelled on in conversation was my own presumed youthfulness. My colleagues all pulled out glasses and then looked at me and said in laughter, “You don’t have to deal with this yet.” As a young professional in my mid-twenties, my viewpoint on what young people need and have capacity for was sidelined as less informed, at least in part because of my proximity in age. As the conversation continued, an attempt was made to give adults the ability to define whether or not a sexual relationship between two minors was consensual or abusive, distancing the ability of minors to categorize their experiences differently. It was even jested that if a young person and their caregiver saw a romantic relationship as consensual that the advocate didn’t agree with, that adult’s judgment was similarly questionable. What wasn’t consciously addressed was the thread of adultism palpable, creating a conscious distrust of youth’s self-determination, and justifying our right as adults to intervene. Entrenched in this forum was the protectionist rigidity displayed by President Grant, and infused were fears that weren’t openly named or specified. Fears that contain biases about youth.

I have to be careful as I write this post that I don’t reinforce the same rigidity that I am critiquing, because there are enumerated forms of violence that young people experience that happen in the ways we fear. Predators that take advantage of sexual ignorance, and power imbalances that corrode consent. And yet, what is not confronted or considered is the place for youth sexuality amidst this backdrop, and youth narrating their own experiences with authority not subordinate to adults.

A question I find myself asking and being asked by young people is where is the place for their point of view, especially as it complicates how we analyze how violence targets and impacts them in alarming rates and through vastly diverse mediums.

In forming the working group I referenced earlier, one survivor seat was created. The survivor selected to speak with authority on the needs that youth survivors have for advocacy was not herself a youth survivor, which is relevant for seeing how adultism shows up subtly and seemingly unintentionally. She was also not from her own disclosures a young person who was sexually active, keeping in line with the makeup of the panel of youth survivors selected to speak to fellow high school students. In both examples sexuality and violence are not concurrent experiences for youth in the psyches of adults, and how youth survivors are represented and talked about perpetuates this dominant perception.

For every young person experiencing sexual violence, there is one negotiating sexual decision making simultaneously.

For every adult ill prepared for their teen to experience a sexual assault, there is an adult equally ill prepared to learn their teen is sexually active.

For every teen keeping their experience of violence from adults intentionally, there are teens similarly fearful to disclose having had sex at all.

The traumas accumulating and the distrust being learned is informed by how these internalizations intersect, not just how they present separately. To bear witness to the consent violations children and youth experience as an epidemic, we have to examine closely what marginalizes their consent more broadly. We have to confront as a culture the unique messaging that encourages keeping young people safe by stripping them of their right to make choices that we support, and the rewarding of their learned submission. It is not disrespectful to adults to react negatively to being controlled, it’s only disrespectful of our absolute authority over their bodies. Their bodies that are constantly under attack, under pressure, under scrutiny, under opinion, and yet not well protected. Not if the measure is safety from abuse. And most especially not if the measure is trust in your body’s integrity and autonomy. By this measure, the rigidity is how we have coped with our fear that we know less about youth than we presumed, and much less that was accountable to how they describe their experiences.

This is drilled home by who we select as the face of survivors, but also what we select as the definition of youth. More commonly youth survivors selected for panels are eighteen and over, compared to a middle school or early high school aged student. We are counting on not just the maturing of age, but also the adoption of our adult perspectives, because the promise is that you will matriculate into all our adult privileges. As is always true with privilege, it is meant to fade out of our awareness and become our perception of what is normal. Adult perspectives are meant to be so pervasive, that we leave off the word adult and just think of our opinions as everyone’s perspectives. And this is where that leaves us, absorbing a viewpoint predicated on marginalizing consent and bodily autonomy for young people, and normalizing any consequent power imbalances. Connecting our real anxieties about their unsafety with our right to have control over their decisions, and the decisions that are considered age appropriate.

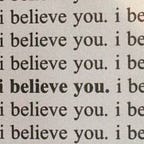

But there can’t be an imagined reckoning with sexual violence if consent is given separate definitions for youth.

There can’t be an embrace of a culture of consent if consent has no true authority.

If power stays in the hands that it’s always stayed in, who really has any new control over their bodies?

Until this blind spot and source of dissonance in our advocacy is called out and deconstructed, we have to question how much consent is a value we are ready to prioritize.

Self determination and consent are two sides of the same coin, in practice and in theory.