The Violence of White Womanhood — on when we’re not accountable

‘Get your people’ is an instruction I take seriously.

The call to be concrete in how we hold ourselves and people in communities we are a part of accountable. The importance of beginning with “us”.

To say that I am disappointed in us as white women is a gross understatement.

To say that our actions and inactions have been impactful even more of one.

We are rarely expected to connect our thinking and emotional responses to the way they shape public spaces, community dialogue, and how we see ourselves more broadly.

When I first started working at a nonprofit serving youth in DC, I participated in a community-based learning space that reflected on the impact of racism in our service delivery.

To participate, you had to accept the starting assumption that as a white person, and particularly a white service provider, you are inherently racist.

You had to openly acknowledge that to live in a culture that is racist, and to have that benefit you, creates internalizations and biases in you.

The point of saying that upfront was to illustrate that you can’t be accountable for a problem you do not believe you contribute to.

You can’t be contributing to racial justice while denying the existence of racism.

That acknowledgement allowed us to use our class time to reflect on how our actions and thoughts contained racism, and it bears repeating in this moment where white violence and gendered violence are inextricably linked in their expression, but not in our solutions or analysis.

I see the cost of time we’ve wasted, of truths we haven’t spoken, patterns that read as episodes because links haven’t been fully demonstrated or spoken publicly.

I see cost and take it seriously — every moment too long something continues instead of ends, every pressure to contain and to normalize and to move past.

Every messenger that meant well.

Every instinct to bury and protect yourself from visibility.

I see cost, and I let myself react to how I’ve confronted and used power, how I’ve been hardened to compassionate responses, how I’ve fumbled chances to hold a microphone and “speak from the hip”.

Whiteness masquerades as everything but, and for white women that means we identify with every label but our own whiteness.

It’s not a term we use or even a set of syllables our tongues naturally utter.

It sounds like a word that feels othering.

It sounds like a word that is inconsequential, or not the point.

Except that it is always the point, best illustrated by how reluctant we are to affiliate with it.

Except, that we have been groomed to affiliate with whiteness — to let our identity be a concept that everyone can recognize and define but us.

It’s not an accident that we don’t see ourselves unobscured, because the nature of whiteness is to be obscured. To hide in plain sight. To redefine itself. To mutate and re-choose its boundaries.

To be weaponized. To be a cause to rally to protect. To mean something sacrosanct.

To be the color of violence we experience, but never blame.

To be the color of violence we execute, but are never blamed for.

There is always force behind whiteness because consent is irrelevant to how it maintains its power.

Whiteness maintains itself with power it already has, and the tactic is generally violence or threat of violence.

The fear it symbolizes is subsumed for white women by the fear used to enlist us in its protection.

Narratives about violence are warped to paint white men as heroes, white women as victims, and anyone else in proximity to whiteness.

Our worth. Our families. Our finances. Our nationalism. Our pasts. Our histories.

To be a white woman is to be a weapon that serves patriarchy and white supremacy simultaneously, while hiding the extent to which we are unsafe, and the power of narratives we wield to further justify violence.

What is often lost in discussions of privilege is its connection to marginalization on a practical level. Namely, that in its basic form marginalization has to do with one’s proximity to power in a specific context. It examines the environmental norms, laws, and resources and how they are determined and enforced.

To have a narrative privileged means that it is spread widely and amplified as the basis of truth.

After a while a frequently said statement feels true, whether or not we are presented with information that counters that message.

Maintaining the myths of our identity means maintaining the pertinent myths of what creates vulnerability to violence.

A lie maintained becomes an internalization, one we reproduce in the minds and bodies of children whose conceptions of the world we directly influence.

Threatening the virtue of white women debases the presumed virtue of their male protection.

How can white male violence be rationalized, valorized, normalized, if it is found to be unwarranted by a perfect cause?

White women in this analogy are not a group, they are a symbol. This distinction matters.

The fragility that describes whiteness is used to distinguish masculine privilege from feminine subordination.

We are the tools for reinforcing dichotomous thinking and dichotomous feeling. Most of the power of this tool is demonstrated by the basic design of our brains. In particular, how they orient threat, and therefore protection from threat.

Whiteness wants us to believe that those who would protect us from harm, are not themselves harm-doers, even though everything in our experiences reveal that thinking as false.

An example that has been called to mind recently for me is To Kill a Mockingbird. Specifically, who benefits from portraying a black man as a perpetrator, and a white woman as a liar. Time reveals two things in the course of that plot — one, that it is not someone of color committing violence against a white woman, and two that a white woman did lie publicly, but not about experiencing sexual violence. The lie is in bearing false witness to who committed that violence, and covering it up at the bequest of a powerful aggressor. In this story, a white father.

I think of this plot when I read about campaign ads appealing to a return of lynching and false accusations of rape against men of color.

I think of this plot when I see video footage of a white woman calling the police on a young black boy alleging a sexual assault in a grocery store.

I think of this plot when I hold our message that kids can’t be perpetrators of violence, and in the same moment read depictions of classmates setting a child of color’s hair on fire, or the Associated Press survey highlighting the regularity of peer to peer sexual violence in K-12 schools.

I think of this plot in memory of the Charleston shooting in which the shooter offered the rationale, “you rape our women”, as his justification for murdering members of a black church.

I think of this plot in memory of a failed attempt to shoot a black church last week in Louisville, and the subsequent deaths of two black grandparents in a Kroger parking lot.

I think of the threatened erasure of trans, gender nonconforming and intersex folks, and continued policy assaults on immigrant communities. Assaults that are violent primarily as a dog whistle — speaking into not exaggerated anxieties about what could or could not happen, but credible anxieties about what has already happened and could happen again or worse.

I think of this literary plot that is banned in many schools not because it contains racial violence, but because it references rape. A censoring that not only silences survivors of violence, but further colludes in maintaining myths about who is and is not violent.

The power that is unleashed and on display now is one of psychological violence, where all one has to do is strum on an internalized myth about what could threaten us, and what responses can be expected.

If violence for you is a feeling, an anxiety, an image being invoked as a white woman, I ask you to pause and ask some questions. Ask your body if its truths are being seen and spoken. Ask your brain if it is engaging in dissonance to protect itself. Ask your conscience if someone in power is being painted as safe and objective so that they aren’t implicated in our violent realities.

Our bodies and brains are designed to respond to threat and threats of threat in a predictable, consistent, immediate way. Those who benefit from that knowledge never forget that. And those who are being victimized by such rhetoric and escalation see and hear the dog whistle being sounded everywhere.

If accountability for gendered violence isn’t connected to histories and uses of white violence, our actions aren’t accounting for the most dangerous abusers of power. Ones who we defend as safe.

Any safety predicated on distorting actual experiences of harm with myths is already weaponized.

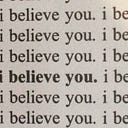

We have a choice to make: deny that we are part of the violence, or call out the myths.

Not choosing is a choice that this administration is counting on.